In late July 1941, Prince George, the Duke of Kent and youngest brother of King George VI commenced a six-week visit to Canada primarily, but not exclusively, to visit airfields which formed part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). The scheme which drew personnel from Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand-and was expanded following the fall of France in June 1940-would ultimately be responsible for the training of an estimated 131,553 Allied aircrew. Most of the training was undertaken in Canada and required the building of new air bases or the upgrading of existing facilities throughout the Dominion. The scheme was administered by the Canadian government and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) with input from the Royal Air Force (RAF). His Royal Highness was accompanied for much of the trip by his Private Secretary, Lieutenant John Lowther, as well as Flight Lieutenant P.J. Ferguson and Group Captain Sir Louis Greig. The latter was a courtier of many years standing, as well as a friend of King George VI. Greig was currently assigned to the Air Ministry. Also in the party were the Duke’s valet and a Scotland Yard detective, Inspector Evans. Wartime restrictions meant that Prince George was permitted to take only two suitcases and a haversack with him for the long trip. The Prince was no stranger to Canada having visited the Dominion with his eldest brother, the Prince of Wales in 1927 to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of the Confederation of Canada. In addition, he had visited Canada alone (including Ottawa) in 1926 and is said to have paid another (private) visit in 1928.

According to the diaries of the Canadian Premier, William Mackenzie-King, George VI himself was the driving force behind the visit, His Majesty being ‘quite decided’ on the matter. Indeed, the Canadian Prime Minister’s diary entry of 11 July states that the Governor-General of Canada, Lord Athlone, informed Mackenzie-King that ‘he thought the King himself had put it forward to give the boy something to do.’ Athlone opined too that ‘the British had approved the project but [he] thought that the suggestion should come from Canada.’ Mackenzie-King demurred and told Athlone (the youngest brother of Queen Mary and uncle of Prince George), that ‘if the Duke of Kent came we would, of course, welcome him cordially.’ Yet, he ‘did not feel, however, [that] I should make a suggestion..’ Ever the politician, Mackenzie-King ruminated that he would be bound to be asked questions as to ‘why I had invited him’ in the Canadian Parliament ‘and [he] did not feel’ that he ‘would be in a position to answer the question satisfactorily.’ More specifically, the reason for his lukewarm attitude towards the proposed visit was subsequently confided by Mackenzie-King to his diary on 17 July: ‘It looks to me like something cooked up between [the Canadian High Commissioner in London, Vincent] Massey and the Palace, something about which the Brit[ish] Govt. nor my own are particularly keen about.’ It must be mentioned that the Canadian Prime Minister was a complex character and his nose was undoubtedly put out-of-joint as a result of what he regarded as a lack of consultation with the government in Ottawa on the part of Buckingham Palace and of Vincent Massey. Even if such soundings had taken place, it is doubtful if Mackenzie-King would have been keen. Furthermore, there was another major factor in the equation, something which indubitably upset Mackenzie-King’s equilibrium: the Duke of Windsor (the former King Edward VIII, eldest brother of Prince George and now Governor of the Bahamas) had also recently made a request to visit Canada, where he owned a ranch in Alberta. The Canadian Prime Minister informed the British High Commissioner in Ottawa, Malcolm MacDonald, that he rather wished that the Duke of Windsor should not come at all but, if he did, Mackenzie-King reasoned that ‘they [the two royal dukes] certainly should not be here at the same time’ as ‘this would give rise to many questionings and might give rise to serious embarrassment.’ Fortunately, the visits of both royalties were scheduled so that they did not overlap. After meeting and entertaining the Duke of Kent following his arrival, the Canadian Prime Minister then planned to take himself off to England for a visit with Winston Churchill and to pay his respects to Queen Mary at Badminton.

Meanwhile, when the tour was announced to the public around 23 July, the British press were casting all such political and court machinations to the side and wrote that His Royal Highness had ‘volunteered’ to make the trip. Prince George and his party flew overnight from Prestwick Airport in Scotland to Rockcliffe Airport, Ottawa in an eighteen-ton Consolidated Liberator Mark I bomber, AM261, of Royal Air Force Ferry Command, arriving at around 10am on 29 July (after a brief stopover in Montreal for breakfast). The flight had taken over fifteen hours and their was little room to lie down or even to stretch one’s legs. The royal visitor was welcomed at Rockcliffe by the Governor-General and the Prime Minister. During a conversation over lunch at the Governor-General’s residence, His Royal Highness admitted to Mackenzie-King that the air journey had been cold and uncomfortable. The Duke joked that although he had been given an electrically heated flying suit, there had been no where to plug it in! The Canadian premier, meanwhile, thought Prince George appeared, ‘pretty tired and nervous.’ For their part, the Canadian press were impressed that the Duke was the first member of the British Royal Family to make a transatlantic flight. They did question him on the possibility of a visit to the United States but Prince George admitted, ‘I am not sure..’ but left the possibility open. The British press, meanwhile, also unhelpfully mentioned that the former King Edward VIII and his youngest surviving brother might meet in Canada.

Whilst in Ottawa, Prince George stayed with his “Uncle Alge” [the family name for Lord Athlone] and his wife “Aunt Alice” [Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, the redoubtable granddaughter of the late Queen/Empress Victoria] at Rideau Hall, the Governor-General’s official residence. Also present in the happy family group were the Athlone’s daughter (and the Prince’s first cousin) Lady May Abel Smith accompanied by her children who were also currently living in Ottawa.

On the evening of 30 July, an official dinner (described by the British press as a ‘State Dinner’) of welcome, attended by seventy guests, was held by the Canadian government in Prince George’s honour at the Country Club in Ottawa. Mackenzie-King was seated between His Royal Highness and the Earl of Athlone and complained that neither was ‘easy to talk to.’ Earlier that day, the Duke had visited the Headquarters of the Royal Canadian Air Force, travelling through the crowd-lined streets of the Canadian capital in his official Buick with police outriders in attendance. Prince George ensured that he waved to the onlookers and this drew sporadic cheers from the “side walks”.

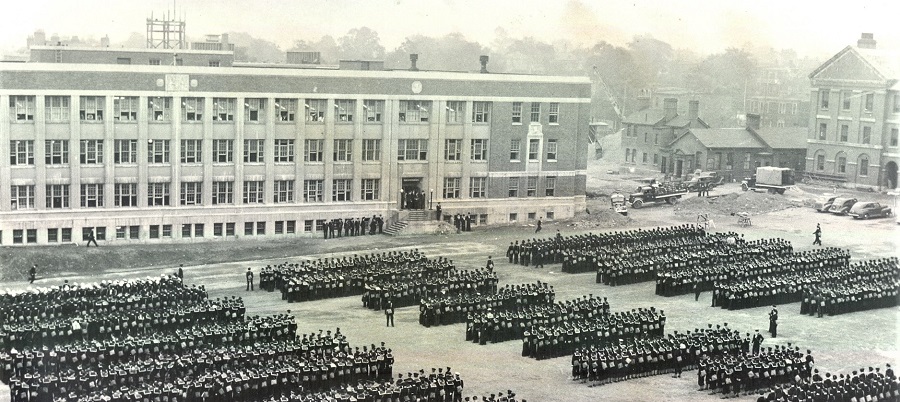

The following day, Prince George was also able to watch a group of Australian and Canadian pilots as they trained at The Royal Canadian Air Force [RCAF] No.2 Service Flying Training School at nearby Uplands. The visit lasted nearly four hours and the Chief of the Air Staff personally greeted the royal visitor, as did a Royal Canadian Air Force Band who provided the Royal Salute, followed by a rendition of “The Thin Red Line”, during which His Royal Highness inspected the Guard of Honour. The Duke then toured the Motor Transport Section, the NCO’s quarters and mess, the swimming pool, the hospital, the airmen’s mess and a barrack’s block. He later had drinks in the officer’s mess before lunching in the dining room. Prince George was placed at the centre of the top table. His Royal Highness subsequently toured the Ground School, the aircraft hangers and the control tower. Each of the airman or ground staff with whom the royal visitor spoke was asked their name, how long they had been in the services, and if they were enjoying their work. Some of the airmen were also questioned about night flying. While earlier reviewing the Guard of Honour, His Royal Highness’ sympathy went out the men who were clad in the heavy regulation uniforms. He paused by Aircraftsman J.E.R. Nadon and asked, “Are those uniforms hot?” Nadon is reported to have replied, “Not too bad sir.” On departing, Prince George mentioned to his Canadian hosts that he had, been ‘impressed by the efficiency of the [Uplands] Maintenance Squadron’. That same day, he also made a tour of RCAF Rockcliffe, going through much the same schedule as at the Uplands airbase. The combined tour of both of these bases amounted to seven hours in total. In the evening, an official dinner was hosted by Lord Athlone at Rideau Hall.

On 1 August, after touring the Gatineau Hills, the Duke was able to watch summer air manoeuvres by some of the many trainee pilots he had previously met at Uplands and Rockcliffe. The trainee pilots were apparently ‘picking up flying time lost during last two weeks’. The latter may have been partly due to the shooting of a Hollywood “movie” by Warner Brothers at nearby Pendleton Relief Field. This included several flying sequences, including one involving an impressive thirty-six aircraft. In the evening, the Duke enjoyed a picnic supper, with Mackenzie-King as host, during a visit to the Prime Minister’s private estate at Kingsmere Lake.

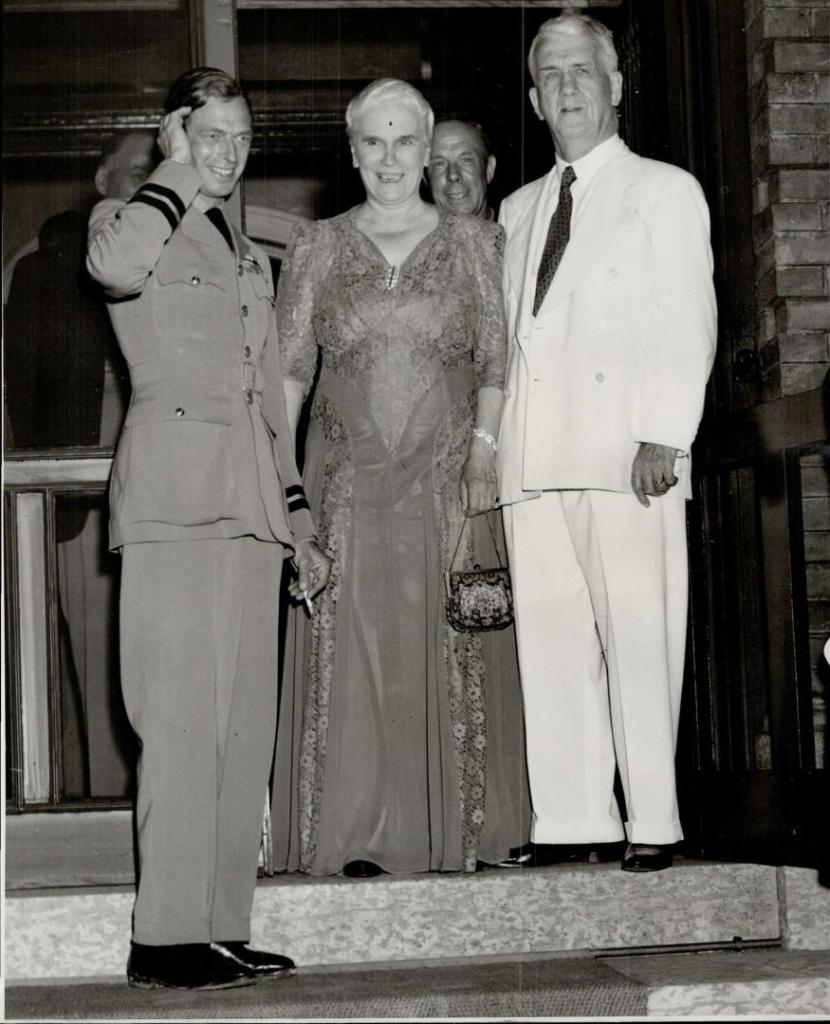

On 2 August, Prince George flew southwards to inspect RCAF Trenton, the largest air facility in eastern Canada and home to No. 1 Composite Training School [No. 1 KTS]. He was introduced to participants of the Aircrew Squadron and Disciplinarians Course. Thereafter, the Duke flew on to make an afternoon inspection of the No.1 Service Flying Training School [SFTS] at Camp Borden, said to be ‘the birthplace’ of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Scores of training planes were on the tarmac as he arrived. He ‘toured the various units’ before enduring yet another “meet and greet” session in the officer’s mess. But it was not only air force personnel: His Royal Highness also met men of the Canadian Armored Division, most of whom had given up there weekend leave to meet the royal visitor. On 3 August, after attending a Sunday morning church service with the Athlone’s, the Duke of Kent flew out from Ottawa to Winnipeg ‘on the first lap of the western section of his tour’. Mackenzie-King, confided to his diary that ‘I think the Duke’s visit, as far as Ottawa is concerned, has gone off very well.’ Praise indeed! The Prince landed at Stevenson Airport, Winnipeg and proceeded to Government House to spend the night. ‘Several hundred spectators’ lined the route of the motorcade. His Royal Highness was entertained to dinner by the Lieutenant-Governor and Mrs McWilliams. It was also at this juncture that it was announced that His Royal Highness would travel to the United States on 23 August to visit President Roosevelt at his private country estate.

On 4 August, a day of high winds which curtailed many training flights, the Duke flew from Winnipeg to Regina, Saskatchewan to pay what the press described as ‘an unexpected visit’ to No.15 Elementary Flying Training School [EFTS]. The stopover was brief, lasting merely 45 minutes. Nevertheless, a guard of honour was hastily arranged (and duly inspected) and the Duke also found time meet ‘civil leaders’ and talk with a group of Americans who had enrolled in the Royal Canadian Air Force. That same day, the Duke and his party flew into RCAF Calgary (Lincoln Park) home of No. 3 Service Flying Training School, where the local Mayor was introduced to His Royal Highness. One hundred and four men stood to attention as the Royal Salute was played and the Duke made time to speak to many as he passed down the line. Prince George later visited the nearby No. 2 Wireless School [WS], travelling through the city centre in a sedan car. At the School he was greeted by a guard of honour and two Royal Canadian Mounted Police astride their horses. The station diary notes that the Duke made a thorough visit of the station hospital where he insisted on speaking to each of the patients about their ailments. He also toured the classrooms and seemed keen to listen in as the students received instruction and later questioned many of them about their experiences. As was often his custom throughout the tour, Prince George then ventured up to the third floor canteen to meet briefly with some of the diners, for he was concerned about the variety of the daily fare on offer and as to whether the portions were sufficient. He asked for copy of the menu and inspected a large walk-in refrigerator filled with fresh meat. The Duke also had an interesting encounter with a Welshman, Harry Jones. While serving as a driver in the army, he had chauffeured Prince George’s great-uncle, the Duke of Connaught and the Duke of Windsor (when Prince of Wales) during their trips to Canada. After a visit to the officers’ mess, the royal party departed Calgary by car for a few days rest at Banff.

Each morning in the mountain resort of Banff, the Duke rose early to enjoy a ten-minute swim before breakfasting with his entourage in the Royal Suite of the Banff Springs Hotel. Whenever he had a spare moment, he would enjoying cantering on a bay horse along the local mountain trails (some press reports state he rode for a distance of around ten miles). On 5 August, Prince George spent many hours ascending nearby 8,000-foot Sulphur Mountain. He took with him a simple picnic lunch of hard boiled eggs and cold meats. The following day he climbed the more demanding 9000-foot Rundle Mountain, in just over six hours, in the company of his detective, Inspector Evans. One of the Duke’s drivers, AC J.S. Botterill, commented on his ‘vitality-I never saw anything like it in my life, so help me.’ Whilst staying at Banff he was also introduced to two members of the indigenous First Nation community, Chief Charlie Bear Paw and Chef Waving Feather. Before leaving the resort at 8am on the morning of 7 August, Prince George thanked Charlie Lambe, who had been his personal waiter and gave him a gift of cufflinks bearing his cipher. Mr Lambe knew the Duke from his time working at Ciro’s night club in London. It was at this juncture that His Royal Highness learned that his friend and ADC, Wing Commander Whitney Straight had been shot down over France. He would later end up in prisoner-of-war camp from which he escaped in June 1942. Meanwhile, the British press commented that there was ‘no plan’ for a meeting between the Duke of Kent and his eldest brother.

The royal trip was by now attracting attention back home in Britain and the London Illustrated News ran a special pictorial feature; while the Newcastle Journal headlined ‘the Duke of Kent in Canada in Colour’ in large capital letters. Meanwhile, the Duke drove himself in a large Lincoln automobile from Banff back to Calgary, from where he subsequently flew to Vancouver and spent an hour inspecting facilities at the airport. Thereafter, it was onwards to Vancouver Island where he toured the RCAF base at Patricia Bay (home to 32 Operational Training Unit). The OTU, as it was referred to, was the ‘last stop’ for aircraft crew in their training protocol. The Duke was greeted by the Lieutenant-Governor, Mr Eric Hamber and a crowd of onlookers, estimated at 3,500. A guard of honour of one hundred airmen were drawn up on the runway for inspection. Prince George and the Lieutenant-Governor would later motor down Vancouver Island to the city of Victoria, a distance of some eighteen miles, where the Duke dined and spent the night at Government House.

Naturally, Prince George could not make a visit to Vancouver Island’s historical capital without a tour of the imposing Parliament House, so next morning he drove there and was met by the State Premier, T.D. Patullo and other local politicians. Later, His Royal Highness had a meeting with Major General Ronald Alexander, General Officer Commanding, Pacific Command at his headquarters at Esquimalt Fortress. His Royal Highness also visited Western Air Command (RCAF) and subsequently lunched with the Commander, Air Commodore A. E. Godfrey at the Union Club. The Lieutenant-Governor and the heads of other branches of the military were also present. Prince George then toured a barracks of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) at the naval base at Esquimalt and later watched an army ‘formation’ display by ‘young militiamen’ at Work Point military camp. In the evening, after dining at Government House, the Duke returned to RCAF Patricia Bay and flew over to Vancouver where he and his entourage stayed privately at “Shannon” the home of Major and Mrs Austin Taylor.

On 9 August, the Duke drove to Richmond, just south of the city of Vancouver, to tour the Boeing aircraft plant, as well as to visit RCAF Station Sea Island, the location for No. 8 Elementary Flying Training School which made use of Tiger Moth aircraft. According to the station diary, “Air Commodore Kent”, inspected both trainees and flying instructors, before ‘thoroughly’ touring the air station.

Thereafter, Prince George and his party undertook an afternoon tour of Burrard Dry Dock where Bangor Class Minesweepers were being built for the Royal Canadian Navy. His Royal Highness also toured the neighbouring North Van Ship Repairs Yard, which had just been re-tooled so as to construct minesweepers, at the behest of the Canadian government. Three new launch ways had recently been built at this site and the Duke was given ample opportunity to inspect the facilities. It is clear from local photo archives that His Royal Highness made time to speak to many of the shipyard workers, as well as some war veterans from World War I. It so happened that the Prince was keen on naval history (having previously served in the Royal Navy as a midshipman) and he was Patron of the Society for Nautical Research. Prince George also met with patients at the Shaughnessy Military Hospital in Oak Street. He was particularly moved to speak to Percy Hart (described as an ‘old timer’ in the Vancouver Sun), who had been hospitalised there with arthritis since 1923. Indeed, he had been a patient when Prince George last visited the hospital with the then Prince of Wales in 1927. News of his visit soon reached locals and as he prepared to depart in his open-topped official limousine, he was surrounded by a large crowd.

The Prince then commenced his journey towards Edmonton by train that evening. En route he again enjoyed at stopover for a couple of days, this time at Jasper National Park, where he dined privately in his private mountain lodge with Charles E Hughes, a retired Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. The Duke also swam regularly in Lake Beauvert and indulged in some climbing. On finally reaching Edmonton by rail on 13 August, the Duke was cheered by thousands as the royal motorcade advanced through the streets of Alberta’s capital city. The welcome was described in the station diary of RCAF Edmonton as the ‘ the most spontaneous and enthusiastic greeting yet received on the tour.’ The Duke first visited the No. 2 Air Observer Corps [AOS] where he toured classrooms at the Radio Technical School. He then inspected No. 16 Elementary Flying Training School where, after signing the register in the Administration Building, he spent a considerable time watching the trainee pilots taking off and landing. Prince George also asked questions of officers, trainee pilots, mechanics and other ground staff during a subsequent tour of the radio room, the hangars and the officers’ mess. His Royal Highness was then introduced to Mr Thomas Bull, a veteran of the Great War. Interestingly, Mr Bull had at one time helped with the construction of a summer house in the garden at Windsor Castle and he was keen to know if the building was still standing. The Duke was pleased to confirm that this was indeed the case, it currently being used by the King and Queen. On departing, His Royal Highness praised the ‘speedy expansion’ of the Air Training Plan.

On the morning of 14 August, the Duke paid a visit to RCAF Medicine Hat, Alberta (home of No. 34 Service Flying Training School). Many of the men at this air station came from Britain. Somewhat unusually, he first attended a Civic Reception in the Town Hall before making a ‘thorough’ inspection of the guard of honour of one hundred airmen. The station diary keeper notes that His Royal Highness made time to speak to around twenty-five of the Guard. Starting his tour in the “Station Sick Quarters”, Prince George’s tour of inspection encompassed ‘practically every building.’ Prior to taking lunch in the Officer’s Mess, the Prince was happy to pose with many of the airmen to have pictures taken. Lieutenant Lowther later wrote a letter of thanks to the Commanding Officer, Group Captain Ellis, stating that ‘His Royal Highness was greatly impressed with all he saw..’ and sent ‘his warmest congratulations on the efficiency of No. 34 Service Flying Training School.’ It was just the sort of morale boost that was needed.

In the afternoon, His Royal Highness flew in his Lockheed-Hudson aircraft to No. 32 Service Flying Training School at Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. The facility had recently been expanded to enable the Allied airmen to spend around sixteen weeks learning to fly Harvard and Oxford aircraft. Once again a large proportion of the trainees hailed from Britain and the local Leader-Post newspaper described the air station as ‘a little bit of Britain transplanted to the broad Canadian prairies.’ There was also a contingent of trainee pilots from Norway. The Duke was entranced by all he saw and spent a ‘considerable’ time up in the ‘watch tower’ watching planes as they landed and took off. This was also the perfect viewpoint to watch the excavation work currently being undertaken to further extend the runways. Prince George later visited the No. I Aircraft Hangar, the Ground Instructional Block, a barracks, drill hall and the station hospital, where he spoke to many of the patients. Word of the royal visit had clearly reached the local population and His Royal Highness went over to speak to a crowd of two hundred onlookers who had gathered outside the air station boundary fence. The Prince subsequently took tea in the officer’s mess where he was formally introduced to the Mayor of Moose Jaw, Mr Corman and the Town Clerk, Mr Craven. The party then left for RCAF Regina (his second visit) where he landed at 7.30pm and spent the night at Government House. During this brief stopover, His Royal Highness was able to meet up with Flight Lieutenant Robert Leavitt, who had spent a week, in May 1940, piloting the Duke in his Hudson aircraft over the north of France. Leavitt had only recently been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for undertaking dangerous reconnaissance work over Norway.

On 15 August, the Duke left RCAF Regina at 9.30am to fly to the No. 12 Service Flying Training School located at RCAF Brandon. The royal party arrived in good weather at 11am prompt. No guard of honour was deemed necessary. Nonetheless, the diary of the air station shows His Royal Highness was still expected to inspect fifty ‘Security Guards’. He subsequently toured the maintenance hangar and the hospital (stopping to ask each patient the reason for their stay and what post they were training for). The Duke then paid a visit to the officer’s mess to to enjoy an ‘informal’ lunch. By 13.30 he had departed to inspect the No. 2 Manning Depot for new recruits located nearby. The royal visitor was determined to be thorough and spent an hour touring the barracks, the athletic grounds and watching a demonstration of the different stages in the training of raw recruits, be it in rifle drill, foot drill, marching or saluting. The royal visitors then returned to the main Brandon airfield to fly eastwards to RCAF Carberry, home of No. 33 Service Flying Training School to make a ‘surprise’ visit and participate in the ‘great event’ of the day, the “Wings Parade” at which the sixty-three Graduate-Pilots of the out-going course received their flying badges. Although this visit was a brief one, Prince George insisted on pinning the Emblem on each of the graduates.

The Prince next progressed to RCAF Winnipeg (less than two weeks after his previous visit to the airfield) the home of No. 5 Observer Corps (OC) and temporary home to No. 14 Elementary Flying Training School. The Duke was asked to present the Starratt Memorial Trophy to the most outstanding trainee of air observers, LAC E.K. Campbell. The latter was also presented with a ‘navigational watch.’ In addition, Prince George met with the other trainees, instructors and officers. The royal party then progressed to No. 8 Repair Depot to view a group of mechanics and engineers at work. Thereafter, the Duke was introduced to civilian pilots attached to the Winnipeg Air Observer School Ltd. His Royal Highness also made a brief speech which was mentioned in the British newspapers, ‘I did not expect the [air training] scheme to be so impressive.’ Apparently, it was already ‘twenty-per-cent more advanced than those in charge hoped for.’ He added enthusiastically, ‘I shall have much to tell them in England.’ Finally, His Royal Highness visited MacDonald Brothers Aircraft factory. MacDonald’s built many of the training aircraft used by the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, including the Avro Avian. The company also undertook airplane repairs on other wartime models such as the Tiger Moth. At the end of what had been a very busy day, the Duke met with members of the Polish Community at Government House, Winnipeg. He was also introduced to a delegation from the Czech-Slovak Military Mission to Canada, who were on a recruiting mission on behalf of the RAF. Many Czechoslovak airmen would subsequently fly for the Allies.

Thereafter, the Duke enjoyed a few days free of duties at the summer home of the late E W Kneeland, a wealthy Winnipeg grain merchant, at Lake of the Woods Island near Kenora, Northern Ontario. He then travelled, early on the morning of 19th August, to pay a visit to the RCAF Fort William, home of No. 2 Elementary Flying School, where he inspected the new barracks block, viewed the recreation room and even toured several storage buildings. Subsequently, Prince George visited the production line of Canadian Car & Foundry which was situated close-by. The plant built Hawker Hurricane aircraft including the Sea Hurricane, which the press described as a ‘navalised version’ of the Hurricane. The royal visitor was pictured for posterity talking to both men and women on the assembly line. This sent out an important message to the world, as women were now increasingly in war production in Canada, the United States and in Britain too. Thereafter, the royal party made a tour of the shipbuilding yard in the neighbouring town of Port Arthur.

The Duke of Kent travelled to Timmins by air on the morning of 20 August (where he was greeted by crowds estimated to be in the thousands and spent an hour 4,000 feet down a gold mine). He subsequently flew four hundred miles southwards to Toronto, where he made a visit to the original “Little Norway”, a training camp and school for expatriate Norwegian airmen then situated at Toronto’s small island airport on Lake Ontario. Prince George later dined with the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario and Mrs Matthews in the Vice-Regal Chambers of Parliament House. Next morning, His Royal Highness paid a ninety-minute visit to the John Inglis munitions plant where he was pictured inspecting a Bren gun (the plant was one of the main producers of this item). He also paid a visit to No. 1 Initial Training School of the RCAF at Eglinton in nearby Scarborough where, in addition to speaking to flying officers, the Prince inspected the kitchen and spoke to the chef about culinary matters, once again demonstrating his concern for the welfare of those serving in the military. There was also rumoured to be a secret RCAF research facility at this site, though whether Prince George visited that establishment remains unclear. In addition, the Duke made a visit to the De Havilland aircraft factory at Downsview Park, Toronto where the legendary Tiger Moth training plane was constructed, as was the twin-engine Mosquito combat aircraft. Both these aeroplanes were vital to the success of the Allied cause and this morale-boosting visit was just what was required.

On 22 August, the Duke of Kent was present at the opening of the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. He made a speech to those attending in which he stated that ‘We are determined and confident that these temporary clouds shall pass and that much better days are to come for all classes of people. The knowledge that Canada is producing an ever-increasing volume of necessary weapons of war is a constant inspiration to the never-flagging courage of our people.’ At this time, Prince George also visited No.1 Manning Depot for RCAF trainees which was located on the National Exhibition site: He spoke to one of the workers in the YMCA canteen, a Mrs J. H. Domine about her work and conditions.

The following day, the royal entourage visited RCAF Oshawa, to open the No. 20 Elementary Flying Training School. The Duke, according to the station diary, was taken to a reviewing stand at the Parade Square and after speaking to officials, he was asked to declare the flying school ‘open’ which he duly did in a ‘short but well-delivered speech.’ Thereafter, he inspected the ‘pupil-pilots’ and their instructors, expressing his ‘admiration for the appearance of all ranks.’ Prince George then viewed motorised military equipment currently being produced at the General Motors Company plant nearby. Whilst there, he again had the chance to meet a group of military veterans. He later returned to RCAF Oshawa to change into civilian dress for his flight to La Guardia Airport in New York. Before departing, the Duke presented his chauffeur for the last few days in Toronto area, Sergeant Earl Baxter, with a pair of cufflinks bearing his distinctive royal cypher. Kind touches such as these did not go unnoticed.

After a brief stopover in New York, where no less than two hundred patrolmen, detectives and traffic police had been assigned to secure the royal party’s route through the city, the royal motorcade proceeded ‘upstate’ towards President and Mrs Roosevelt private Springwood estate, at Hyde Park, situated on the eastern shore of the Hudson River, some four miles north of Poughkeepsie. The Duke arrived just in time for dinner that evening. As the Duke confided to waiting reporters at La Guardia, this was the first time he had met the President since a previous encounter in the Bahamas in 1934 when he and his wife, Princess Marina, were on their honeymoon. On Sunday, the Prince’s host took his guest on a tour-the press described it as a ‘preview’-of the newly-completed Franklyn Roosevelt Library. The President was keen to ensure that his royal visitor viewed an eclectic selection of the items on display-mostly statues and art work-for this inaugural exhibition at the Library. Further ‘highlights’ included the chance for a royal dip in the Roosevelt’s private swimming pool up and being driven by Roosevelt in his specially-adapted car on a tour around the two hundred acre estate. In the evening, the Duke and the President travelled by ‘special train’ overnight to Washington D.C., arriving at Union Station the morning of Monday, 25 August. The Duke and his party then flew immediately down to Virginia from Anacosta air station, visiting an operational unit at Langley Air Force Base, as well as touring the Navy Yard at Norfolk (‘the most important naval centre on the Atlantic seaboard’) which was currently being expanded to better supply the combat ships that were required. At the latter the Duke was greeted in person by Admiral Manley H. Simons, District Commander of the 5th Naval District and cheered by workmen as he progressed through the yard. There was a visit too to Newport News Shipyard which specialised in the construction of aircraft carriers. His Royal Highness returned to Washington to spend an overnight at the White House. A dinner was held in Prince George’s honour (attended by eighteen guests who included his kinsman, Dickie Mountbatten, his wife Edwina and Harry Hopkins, who frequently travelled to Britain as Roosevelt’s “envoy”). That the President and the Duke of Kent had managed to spend some “quality” time together was seen as advantageous to the British cause, for with the United States not yet having entered the Second World War, the King and Churchill had been particularly anxious to sustain the “special relationship” between Britain and its long-time ally.

Meanwhile, Mrs Roosevelt had confided to the press that the Prince, like his brother King George VI, ‘was very shy and thoughtful.’ Nevertheless, His Royal Highness remained determined to raise Britain’s profile in wartime in the States: The following morning he was given the ideal opportunity: After a brief tour of the Presidential mansion and West Wing, the Duke paid a visit to the National Press Club where he made an upbeat speech underlining his confidence in an Allied victory. He emphasised that ‘the more material aid the United States furnishes, the quicker Britain will win’ adding that morale in his homeland ‘was good’. On a lighter note, His Royal Highness teased his American hosts that he had not seen an orange or a banana for months until his recent arrival in Canada.

Prince George subsequently visited Baltimore, on 26 August, the home town of the Duke’s sister-in-law, Wallis Warfield (whom the local Mayor insisted on calling “Our Wally”). His Royal Highness inspected bombers being built for the Royal Air Force at the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Plant. Again, this factory had recently been enlarged due to the Allies desperate need of combat aircraft, such as the A-22 Maryland Bomber. During the visit, the Duke addressed some of the 13,000 workers at the plant and imparted another rousing, patriotic message, ‘You are playing a vital part in our fight. Every hour you work not only saves the lives of our men, women, and children, but brings victory nearer.’ Before leaving, His Royal Highness was introduced to one hundred and fifty officers of the British Merchant Navy. He also inspected Canadian troops at nearby Camp Holabird. Tom Hanes, an American journalist was allowed to accompany the Duke throughout the Baltimore visit and described him as ‘just another good guy…who is trying his level best to handle a tough job.’ Hanes asked Prince George for his views on the current American defence effort: ‘Marvellous. The spirit is wonderful. Please say for me that we deeply appreciate the tremendous accomplishments of American industry.’ The journalist noted that the royal visitor was drinking bourbon and the Prince admitted he did not care for “Scotch”. However, he had praise indeed for American journalists, feeling that they ‘ have given me quite friendly treatment…They’re fine fellows.’ A deft public relations treat on the part of the Duke!

On 27 August, Prince George returned to Canada to visit Hamilton, Ontario, where he was greeted by cheering crowds as he visited Westinghouse’s Electric Plant. Originally a small appliance factory, the facility had been re-tooled and expanded to produce anti-aircraft guns and other components, including many for the Mosquito Bomber. In the afternoon, he paid a visit to RCAF Hamilton (Mount Hope) and spent an hour reviewing No. 10 Elementary Flying Training School. He ended the day by inspecting and subsequently spending an overnight at RCAF Jarvis, the Ontario home of No.1 Bombing and Gunnery School, close-by the north shore of Lake Erie. Meanwhile, at Badminton in Gloucestershire, the home of the Duke of Beaufort, and temporary wartime residence of Queen Mary, Mackenzie-King was quizzed by the Dowager Queen about the Duke’s visit. Her Majesty had been following her youngest surviving son’s trip with great interest and showed the Canadian Prime Minister a selection of newspaper clippings, including one of Prince George at Rideau Hall with the Athlone’s. Mackenzie-King enthused that ‘some very fine movies’ had been made of the royal tour, although he also divulged that the Duke of Kent had informed him ‘that he never liked to see himself in a movie.’

On 28 August Prince George was photographed with John Mack from Britain as he toured a No. 1 Technical Training School at RCAF St Thomas, near London, south-eastern Ontario. The site had a capacity to train up to 2,000 men at a time to work as skilled ground crew. The following day, His Royal Highness made an ‘unexpected visit’ to RCAF Cap de la Madeleine, the home of No. 11 Elementary Flying School. The Duke’s plane hade been forced to land here due to poor visibility. The air station diary notes: ‘Unfortunately for us the royal visitor had to be rushed to the [train] station at Three Rivers to catch the Quebec train [for onward travel by air to St Hubert aerodrome, Montreal]. Consequently he didn’t have time to visit our school.’

When the Duke landed at St Hubert aerodrome it was already twilight. So began his forty-hour visit to Canada’s (then) largest city. A motorcycle escort accompanied his official car, flying the Ducal standard, to Montreal’s City Hall where His Royal Highness signed the city’s famous Golden Book and was guest of honour at an evening reception (presided over by the Mayor, Monsieur Adhemar Raynault and attended by ‘high military and civic dignitaries’.) Monsieur Raynault praised the royal visitor to the local press on his ‘very fluent French’, as well as on his interest in matters pertaining to French Canada. That evening, Prince George spent the night at the aptly-named Windsor Hotel, where five hundred people crowded the hotel lobby in order to try and catch a glimpse of the royal visitor as he entered (a further 2,500 were also waiting outside so the Duke waved from a window of his suite to acknowledge their cheers). Meanwhile, the Montreal Gazette revealed that traffic around the hotel had been ‘rerouted lest it rouse Duke’. The following day, 29 August, was packed with engagements including a visit to No. 1 Wireless School at RCAF Montreal (currently housed in what had been the Nazareth School for the Blind) where the Duke was introduced to a large group of Australian and New Zealand airmen. Prince George also toured the classrooms and later lunched in the officers’ mess. During a tour of the canteen, he asked a member of staff how much beer and ale was being sold. The royal visitor then moved on to visit the huge Canadian Pacific Railway manufacturing and repair facility, known as Angus Shops. This depot-which was set over 1200 acres-was also now used to produce Valentine tanks for the war effort. His Royal Highness also paid a visit to Ferry Command: this Montreal-based organisation, operating out of RCAF Lachine (Dorval), made use of civilian pilots to deliver thousands of bombers built in Canada and the United States, fresh off the production line, to Britain during its darkest hour. Many of the transatlantic routes used by the crews (who also included trained navigators and radio operators) were new and experimental as the airmen learned to cope with dangerous conditions such as fog, blinding rain and heavy turbulence. His Royal Highness also visited the Fairchild Aviation aircraft at Longueuil, Quebec (where the Fairchild PT-19 training aircraft were being built). A selection of eleven different types of plane built in Canada were available for His Royal Highness to inspect. The Duke then made time to visit the look-out at the top of Mount Royal, where he viewed a monument erected to commemorate the visit of the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in May 1939. A tea was held in the nearby “chalet” which was attended by city councillors and Mayor’s of some of the neighbouring municipalities adjoining the City of Montreal. Indeed, the Duke shook hands with ‘scores of the cities leading citizens’ during the one-hour reception. Prior to departing, the royal visitor reviewed a large contingent of air cadets and complimented them on their ‘smart appearance.’ The Ottawa Citizen newspaper revealed that as a kindness to His Royal Highness, a Montreal department store, Henry Morgan and Company, opened specially ‘after hours’ to allow the Duke to do some shopping which included the purchasing of some fountain pens. Not surprising given that the press described this day in Montreal as ‘the busiest day of his Canadian tour.’

The Prince departed St Hubert airport at 11am prompt on 30 August in a Grumman Goose amphibian aircraft for the town of Sorel, in south-western Quebec, where he toured Sorel Industries. This company was currently ‘turning out 25-pound field guns’ for the British Army. This was followed by a visit to the town’s Marine Industries which was involved in the construction of small warships (Corvettes) as well as the building of the largest all-welded vessel ever built in Canada. The New York Times revealed that Prince George was thereafter enjoying a brief sojourn at the fashionable Quebec holiday resort of Murray Bay, east of Quebec city. He was actually staying at Saint-Irénée-Les-Bains at the turreted chateau of Mr Pierre Francois Casgrain, a former Speaker of the Canadian House of Commons. For some of his time here, the went for a ‘canter’ along the Hotel Manoir Richelieu’s bridal path. On another occasion, he enjoyed a post-prandial four-hour, fifteen mile hike through local woodlands with the faithful Inspector Evans at his side. Nor was the Duke’s downtime carefree as back in London, his wife, Princess Marina, was undergoing ‘minor eye surgery’ and had cancelled her engagements for the next two-weeks.

On 2 September the Prince had resumed his tour, departing Lake St Agnes in his sea-plane for a tour of the Maritimes and an examination of eastern seaboard defences. The royal party first travelled to New Brunswick for a two-hour visit to No 8 Service Flying Training School, Moncton. This included a reception, a lunch with the officers, followed by ‘an Inspection of the Station.’ Later that afternoon, Prince George and his party flew over the Northumberland Strait to RCAF Summerside, on Prince Edward Island. This was the home base of the No. 9 Service Flying Training School. The Duke was there to inspect the new No. 2 runway. However, 70mph winds led to his Grumman aircraft having to land on a field of grass in the centre of the aerodrome, rather than on the new runway. Subsequently, His Royal Highness took tea in the officer’s mess and met members of the ‘permanent staff.’ Then, as the winds remained fierce, it was decided that Prince George would travel by car, rather than by plane, to his next engagement at RCAF Charlottetown (also on Prince Edward Island). This change in mode of transport meant that he was one-and-a-half hours late for his next engagement. This was somewhat unfortunate as Members of the Provincial government were kept waiting, as was the Lieutenant-Governor, Mr Le Page and the Commanding Officer Eastern Air Command, Air Commodore Anderson. Charlottetown was the home of No. 32 (Royal Air Force) Air Navigation School (ANS), as well as the No. 31 School of General Reconnaissance. The Duke was particularly interested in the work being undertaken there and in the equipment being used.

On 3 and 4 September, the Duke of Kent visited Halifax, Nova Scotia where he toured the RCAF facilities at Eastern Passage (east of Dartmouth), the headquarters of Eastern Air Command. He met a group of Canadian air force pilots who had recently returned from manoeuvres in England, as well as airmen who served in the Royal Air Force and the Fleet Air Arm. Most of these individuals had been involved in recent the Battle of Britain. The Prince also took the salute during a flypast and presented a new insignia to the No. 5 Squadron (featuring a gannet) at its base, RCAF Dartmouth. This squadron specialised in anti-submarine activities. In the evening, the royal party were entertained to dinner by the government of Nova Scotia. Next day, His Royal Highness inspected the “Stad”, as the local naval barracks were often referred to (official name HMCS Stadacona) and he also toured the naval dockyard. In the afternoon, Prince George departed Halifax and flew to the city of Quebec, landing in the harbour in his amphibious plane. He then drove to The Citadel, the Governor-General’s residence in Quebec City, where he was again entertained by his Uncle Alge and Aunt Alice. After attending yet another official dinner, the Duke rose early the following day to a packed schedule with six hours of engagements during which His Royal Highness visited an arsenal, before moving on to the No. 4 Manning Depot [RCAF] where he chatted to an aircraftsman in the barber shop. He also toured the depot medical clinic and spoke around a dozen patients. After lunching with the Depot Commander, the royal party made a a tour of the Valcartier Camp-some twenty miles distant-home of the Canadian Infantry Training Centre. The Duke also caught up with correspondence and wrote a letter of thanks from the Citadel in his own hand to Mrs Roosevelt ‘for all your kindness and hospitality during my visit to the USA.’ The Prince had ‘enjoyed my visit to Washington so much, I only wish it could have been longer.’ He was returning home ‘next week full of wonderful impressions of what is being done over here to help our cause.’ Thereafter, on 7 September His Royal Highness enjoyed an afternoon of culture when he accompanied his Uncle Alge and Aunt Alice on a visit to the Museum of the Province of Quebec. In the evening, the trio were guests at a dinner given by the Lieutenant-Governor of Quebec, Major-General Sir Eugene Fiset at his official residence, Spencerwood.

The Duke subsequently broadcast over the radio, mostly in English, but with a portion in French, on the evening of 9 September, prior to leaving Quebec City en route to Newfoundland the following morning. Prince George said that ‘the inspiration I have received from these few weeks among you gives me additional confidence in leaving your shores..’ He also praised the ‘remarkable achievements of the Commonwealth Air Training Scheme in Canada.’ His Royal Highness also mentioned his brief visit to the United States and opined that out of the war would surely be ‘born a closer friendship and unanimity among people who spoke a common tongue.’

On 12 September the Duke of Kent flew into Newfoundland’s Bay Bulls Big Pond from Sydney, Nova Scotia in a flying boat accompanied by two escort planes. He was due to have arrived on 10 September but was delayed, yet again, by the inclement weather. During his unscheduled time in Nova Scotia, Prince George toured a steel plant in Sydney which was involved in the production of war materials. He was also able to learn of the anti-submarine operations being conducted out of RCAF Sydney. In Newfoundland, His Royal Highness was greeted by a Guard of Honour from the Newfoundland Militia and lunched with the Governor (Newfoundland was at this stage not part of the Dominion of Canada and was proud to describe itself as the “Old Colony”), Vice-Admiral Sir Humphrey Walwyn at Government House, in the capital St John’s. In the afternoon the Duke proceeded to the Feildian Athletic Grounds and took the salute at a parade of Royal Navy, United States and Canadian military forces, as well as a contingent of Newfoundland Great War Veterans and of the Newfoundland Militia. Later, His Royal Highness visited the Grenfell Institute to meet more Allied servicemen and Newfoundland naval recruits. He spoke to many and was again particularly concerned about arrangements for their welfare and comfort. Then-in the company of the Governor- he motored to Bay Bulls Big Pond and departed for the journey back home to Britain. The Duke, it was said, had ‘encouraged…by word and deed [others] to carry on in their endeavours…’ in wartime.

On the return journey to England, following his 15,000 mile tour, the Duke took the controls of the Liberator bomber he was travelling in ‘for a short time’. The press were also keen to note that His Royal Highness ‘insisted’ in observing the usual travel etiquette such as showing his passport. The Prince also remembered his family from whom he had been separated for so long. His wife Marina received the gift of twelve pair of silk stockings, whilst his eldest child, Edward received the present of the model of an American bomber. Asked by the British press, on his return home on 13 September, about his return flight from Newfoundland, Prince George observed that “It was like flying back from Paris in peacetime. There wasn’t an incident.” Meanwhile, there were calls by some newspapers for the Duke to be sent out to Canberra as Governor-General, his previous appointment having been ‘postponed’ in 1939 due to the outbreak of war. A political commentator of one journal reasoned that ‘as he recently crossed in safety to Canada’ then ‘the risk of his now going to Australia could not be much greater.’ However, these comments were largely overlooked when the Duke spoke movingly in a BBC radio address on 17 September of the success of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan: ‘this great air training organisation…which is not surpassed anywhere in the world’. He also enthused that ‘I found everywhere…an admirable spirit of comradeship, a deep consciousness of the gravity of the crisis which confronts us, and an eagerness to get on with the job, and see it through, no matter what personal circumstances it might entail.’ His Royal Highness added that ‘I was glad to be able to tell the King what I had seen and what I had heard in Canada.’ Prince George ended his address by noting, ‘the magnificent spirit and resolution of the whole Canadian population impressed me deeply.’ The Dominion Office in London stated the Duke’s tour was ‘most successful and widely appreciated.’

There are photos of HRH Duke of Kent in Nova Scotia on this visit to Canada. I showed them to his son, HRH Prince Michael of Kent.

LikeLike